This Plastic Life

In the middle of Japan’s economic dominance in the ’80s, city pop emerged as a paean to consumerism. Four decades later, the vapor trail of nostalgia and that era’s lost promises have found new life. Just don’t blame it on the algorithms.

Gabriel Kuo May 25, 2021

The YouTube view counter on Mariya Takeuchi’s “Plastic Love” has surpassed 60 million, a staggering number for an almost forty year-old song. It won’t eclipse the 2 billion views of Psy’s “Gangnam Style” anytime soon, but considering that the song has had no hypnotic video (only a still photograph of Takeuchi accompanies the video link), no label backing, and no mainstream press, speaks to the resurgence of early ’80s-era Japanese city pop.

Even more curious is the evergreen nature of the comment board, with a new entry appearing almost every few hours. There have been numerous subreddits devoted to the singer and the single. Pre-Covid, Mariya parties were held in cities as distanced as Los Angeles and Berlin. The original vinyl pressing of “Plastic Love” goes for a grailed price of no less than 350USD on Discogs. In 2018, Vice declared Takeuchi’s single “the best pop song in the world”. How did this relatively obscure track grow to relevance after all this time?

In 2017, user ‘Plastic Lover’ uploaded an extended fan-made remix of “Plastic Love” to YouTube. As the algorithms churned, the view counter and likability meter started revving up, no doubt due to the robotic recommendation engine cranking away behind the screen. Buoyed by meme momentum and subreddit chat threads, the video quickly went viral and surged in popularity. A lawsuit over the video’s accompanying image copyright led to the link being taken down at 24 million views, but was then re-uploaded in 2019 after a settlement was agreed upon with the photographer Alan Levenson for his then uncredited photograph used on the video.

Detractors point to the machinations of algorithmic curation and big tech’s manipulation and control of your digital footprint, but that doesn’t fully explain the phenomenon. Speaking to The Japan Times, Kevin Allocca, head of YouTube’s Trends division, explained, “YouTube’s recommendation systems try to match each viewer to the videos that they are most likely to watch and enjoy, providing a real-time feedback loop that cater to each viewer’s varying interests.” But, Allocca doesn’t believe the enormous success of “Plastic Love” is entirely due to cold code. “In reality, music fans who are exposed to the song listen to it and ‘like’ it, and YouTube’s recommendation systems simply incorporate such positive signals,” he states.

Analytics aside, “Plastic Love” has survived its initial irony and meme half-life to ascend to something more remarkable – emotional sincerity and an imagined nostalgia for a forgotten era. The comment section routinely casts axioms such as “False ’80s memories are better than true 2010s memories” and “Remember, the algorithm only learns from you — do not thank the algorithm — you are here because you are you.”

Takeuchi had established herself as a bankable recording artist by 1981, releasing five successful full length albums to that point, at times working with American collaborators David Foster and members of Toto. Thereafter, she took a break to start a family with Tatsuro Yamashita, who is widely credited as the dominant architect of city pop. She returned in 1984 with Variety, which was produced by Yamashita. The album debuted at #1 on the domestic Oricon album charts, and though “Plastic Love” was released as a single, it only reached a modest #86 on the chart.

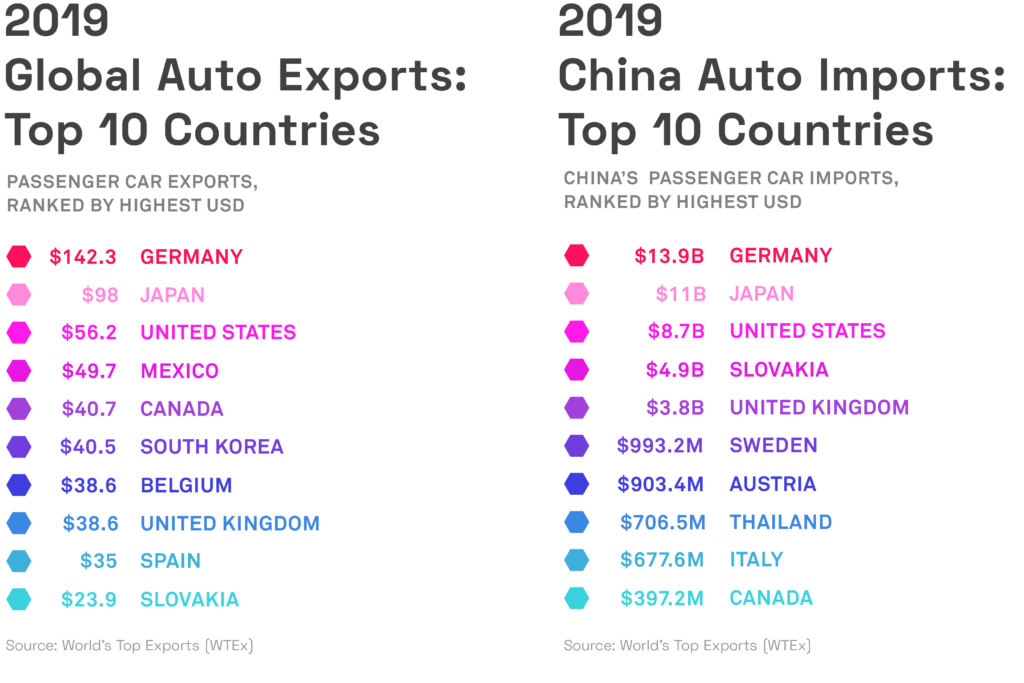

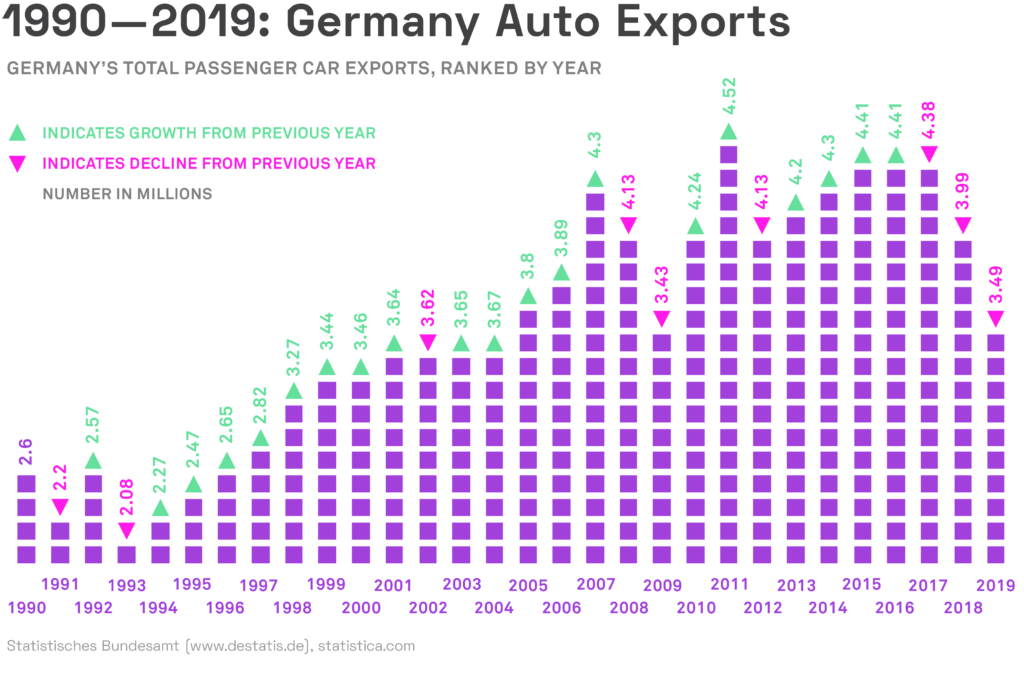

That year, Japan was in the midst of an expansive economic run. Driven by manufacturing, automobile exports, and the technology boom, Japan was funneling plenty of capital into the music industry, with a nation of middle class consumers ready to enjoy the new leisure class. This age of prosperity created watershed cultural industries like the video game revolution, anime and manga, and J-Pop, a precursor to K-Pop.

In the late ’40s and early ’50s, as Japan was rising from the ashes of World War II, its emphasis on the industrialization of raw materials like steel and cotton, combined with massive education reform, created a growth model that, by the mid ’60s, resulted in an era of unparalleled opulence. The Western fear of Japan turning to Communism propelled a stream of global trade-friendly policies and fiscal protections that Japan utilized to mount massive economic and cultural revitalization. Japan repaired and developed their national infrastructure at a rapid pace, creating highways, high speed railways, underground subways, and sophisticated urban architecture. A complete overhaul of its lending and debt policies led to enormous industrial growth, with heavy assistance from lenient deregulation laws for corporations.

At the heart of this “economic miracle” was the Foreign Exchange Allocation Policy, a framework which dictated exports over imports, further shaping its markets for domestic dominance. The first automated teller machine (ATM) debuted in Japan in 1966, enabling cash withdrawals and automated bank loans with credit cards. The streets were paved and cash was flush. Japan had industrialized faster than even they had anticipated, and consumption flourished.

Japan’s efforts in infrastructure paved the way for technology to enter in the ’70s and amplify sectors of society, as apartments needed color televisions, and offices needed xerograph and fax machines. Subverting the German Krautrock sound, the pioneering electronic band Yellow Magic Orchestra was experimenting with a new computer-based soundscape and began to influence an array of Western artists and genres to come, everyone from Duran Duran to Afrika Bambaataa. The contemporary sound of Western ’80s popular music owed much of its character to an emergent wave of sophisticated electronic instruments, as Roland drum machines and Yamaha keyboards were exported from Japan.

During this time, leisure-driven AOR-rock began to dominate mainstream radio airwaves, captured by artists like Steely Dan, Toto, and Supertramp. Japanese producers quickly appropriated the airy, breezy song structures and fortified their version of the genre with messaging reflective of the newfound social privilege, professional ambition, and casual love that defined much of the capitalist middle class in Japan.

City pop can best be described as a Japanese amalgamation of post-war American musical genres: ’50s surf rock sensibilities, ’60s folk sincerity, ’70s funk bass, and ’80s disco buoyancy. But most of all, it simultaneously mirrored the American AOR airwaves during the early ’80s. Heavily integrated into city pop was the accompanying visual element, an aspirational landscape with leisure and indulgence at the core of its messaging. The new autonomy and mobility for this emerging middle class translated to enormously successful commercial markets, and as young Japanese professionals bought more cars, took more high-speed rail rides, and flew more intercontinental miles, so came the need for high fidelity car stereos and portable cassette and compact disc players, all of which were quickly exported to the West in massive volumes.

These new technologies differed from traditional high-fidelity audio components in terms of portability and proximity to the speakers, either in your car or directly on your ears with headphones. The recording industry embraced digital audio and pivoted to the new near-field sound experience by using increased and generous amounts of overdubbing and echo, recording vocals front and center, and pushing bass signals a bit further back in the soundstage.

New machine instruments lent crisper and cleaner tonal sequencing, while everything was mastered with enough reverb to glue the mix together. These audio recordings worked in tandem with a modernist design language and advertising-level photography of geometric swimming pools, pristine sports cars, crisp loungewear or eveningwear, and fantastical city skylines. All of which infused momentum and vitality to a powerful new genre that was not only reflective of Japan’s post-war economic resilience, but gave shape to an imagined future of cars, cocktails, and social success.

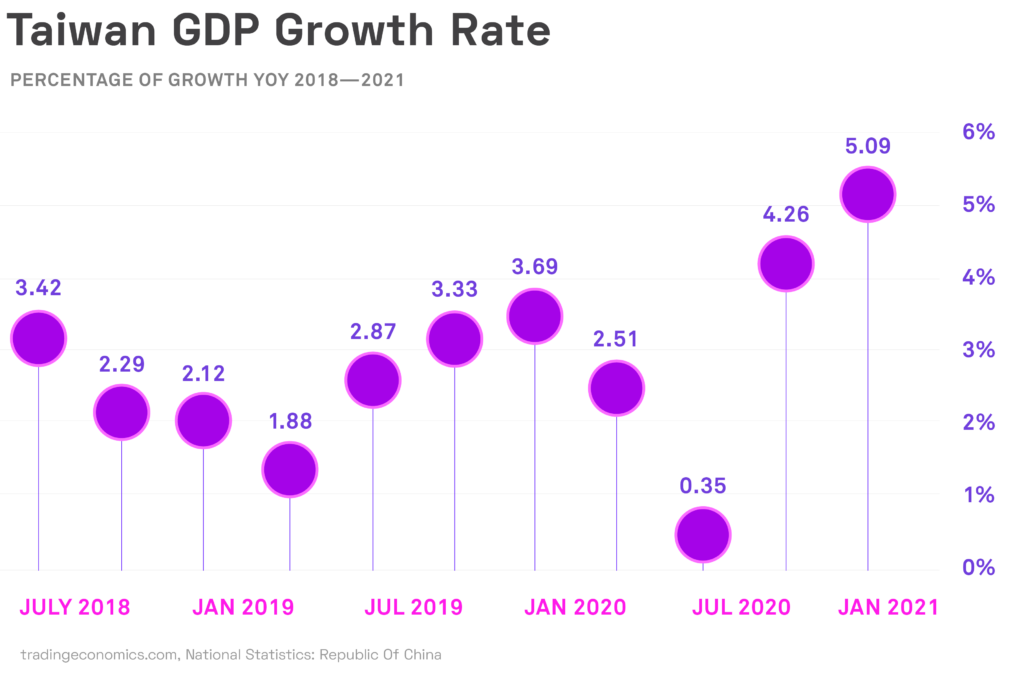

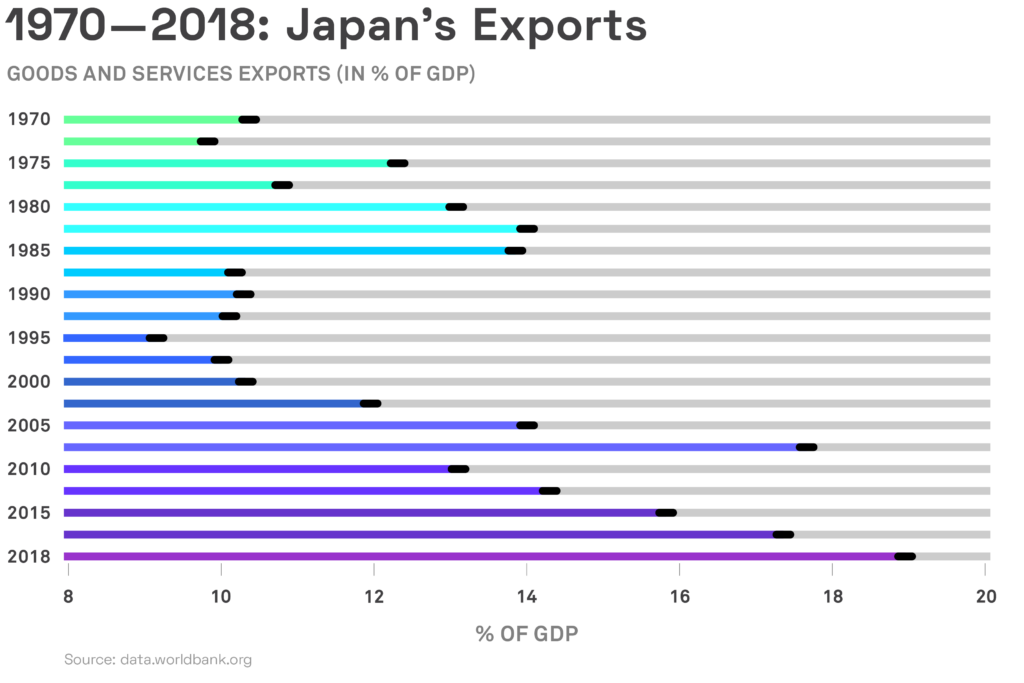

This turned out to be the big bubble. Thereafter, beginning in the early ’90s, Japan’s GDP steadily declined, and by 2000 they had sold back to New York most of the midtown skyscrapers they had triumphantly bought in the ’80s. Japanese real estate and stock market inflation between the mid ’80s and early ’90s signaled the demise of a once booming economy, much as a result of the 1985 Plaza Accord which inflated the Yen against the US dollar and German Deutsche Mark.

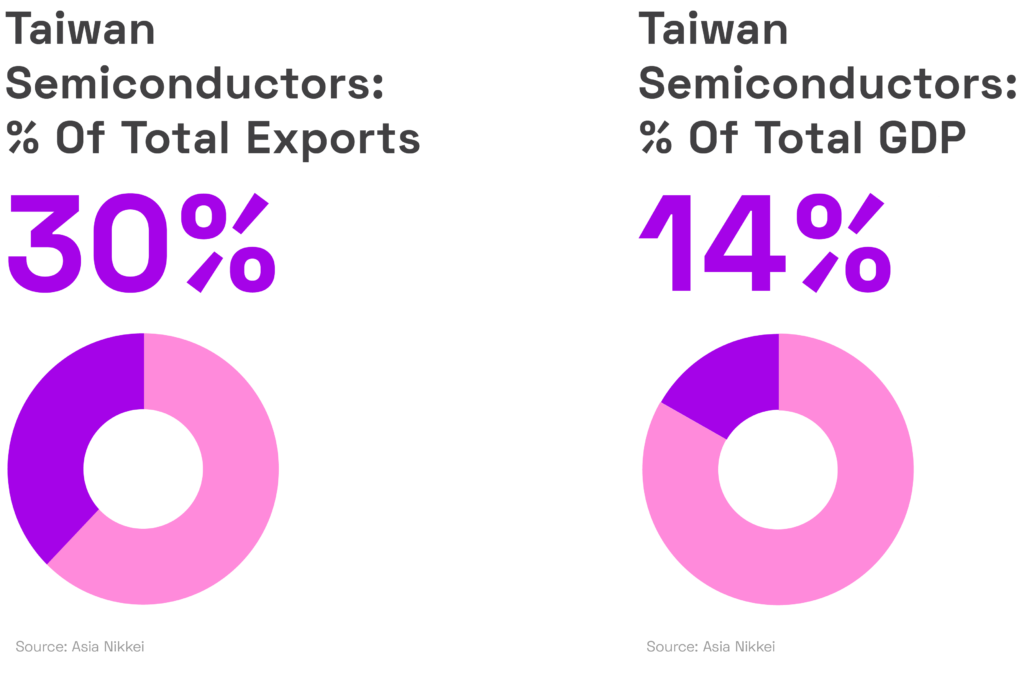

As the ’90s further unfolded, Japan nose-dived into decline due to massive inflation and loss of export market share. South Korea was emerging as a forceful manufacturing and trade competitor, and similar to Japan, it was aided by several American economic and trade policies implemented after the Korean War to stave off its draw to Communism. And as the new century began, J-Pop ceded its popularity to the now towering K-Pop industry, as South Korea began to increase its tech and auto market share and grow its GDP with sizeable Western exports, similar to Japan’s economic strategy. City pop didn’t age very well, as the next generation of young Japanese viewed the genre as tacky and pretentious, often referring it to ‘shitty pop’.

Culturally, much of the ’90s felt like a reaction to the previous decade’s unfettered consumption, and in the West, the music industry as a whole pivoted hard towards the counterculture and emo ethos of grunge, hip-hop, and identity pop. That cynicism spliced into the anxiety of globalization and false wars of the early 2000s, and by the time the 2008 financial crash landed, a new internet generation started to question many of these artifacts of economic hierarchy and outdated power structures.

New ideas were taking shape in bedrooms and dorm rooms, as disruptive companies like Amazon and Facebook began to gain significant market share against blue chip ’80s corporate stalwarts like IBM and Walmart. In the music scene, vaporwave emerged as an anti-capitalist sentiment that aligned with the seismic shift of corporate culture bowing to the upstart nature of an adroit and emerging online sector.

Vaporwave first arrived as an online microgenre with mostly meme-level attention and tumblr recognition. An electronic hybrid genre consisting of detuned, chopped and screwed smooth jazz, pop, and lounge R&B, all hovering around 80-100 bpm, vaporwave derives much of its source material from signature ’80s big production heavy pop and R&B, and of course, Japanese city pop. Anonymity is pervasive, as a single artist will commonly publish under several aliases, further emphasizing the wraith-like ownership of the content. Geography has no bearing, as artists create sounds and produce albums from Chile to Hong Kong to Holland.

Given its inherent nature as a pure digital construct, it grew at a rapid pace, with feverish pockets of the internet taking root on 4chan, last.fm, and bandcamp, where limited cassettes are self-produced and distributed. Laptops and home recording gear could now assemble and perform with striking exactitude what multi-thousand dollar recording studios and hi-end graphic agencies produced a couple of decades prior.

Aesthetics are central to the genre, with much of the imagery ripped from aspirational ’80s consumerist Japan (neon cyber-cities, pristine shopping malls, business hotel suite interiors, video game riffs, and jubilant anime motifs), which in turn are photoshopped alongside spartan computer graphics extracted from the visual language of early desktop publishing. Occasionally there is a Greek column or Roman bust, a wry nod to European neo-classicism and its re-contextualized role in ’80s plaza architecture. Song and album titles are frequently typeset in Japanese, and the sounds of lushness derive mostly from Asian mega-mall nostalgia (hissing water fountain sculptures and soft-toned hostess greetings), with all the phantom tones verging on subliminal. It is the uncanny valley of a memory from a forgotten modernist and opulent past: a nostalgic phantom limb, an unreliable narrator.

Regardless of form, a basic keystone of vaporwave seems to be the sonic betrayal of capitalism. “Vaporwave is the musical product of a culture plagued by trauma and regression in late capitalism,” states author Grafton Tanner, adding that vaporwave artists are “skeptical of capitalism’s promise to redeem us in the name of material goods and of the nostalgia that hangs over an era obsessed with the clichés of history.”

The genre peaked around 2017, right around the same time ‘Plastic Lover’ uploaded his iteration of “Plastic Love” to YouTube. The trending arc of vaporwave that originated from chat room hysterical cynicism had, in a few short years, evolved to a communal sincerity, a submission to its source material and its original allegory of economic prosperity and class mobility. “Plastic Love” uncloaks the colossal collective melancholy of a now distant era defined by the hope of consumerism and the birth of incredible and universal digital tools, tools and language that now dominate our normalized reality: the artificial intelligence of the home computer, the fantastical orgy of visual special effects, the idealized human within the reflecting pool of branding and advertising.

The goal of city pop was never to solve an emotional need, but rather to give consumer flatness a dimensionality that would inhabit the sounds of a sanguine, simulated future and sell as many records as possible. For a while it did just that, and the genre served well as an anthemic fulfillment of Japan’s national success, reflective of the economic miracle it had just pulled off.

It’s clear why vaporwave chose to mine city pop and ’80s Japanese iconography — the old economic and legacy corporate ideology was now weak and defanged. What better proclamation of disenchantment than the appropriation of sounds and visions from that era? The mere gesture of taking a city pop sample and tuning it down to 80 beats per minute speaks to the decline and sobriety of a society waking up thirty years after the boom. Only in retrospect do we see the vapor trail of the imagined landscape of our idealized self. What “Plastic Love” has managed to achieve is noteworthy if only for its ability to reveal the unvarnished emotional core of this idealism, the hope for some imagined future and the promise of intimacy, however synthetic.

Gabriel Kuo is the founder and editor of Atmota. He is the editor of The Strokes: The First Ten Years and A Vulgar Display Of Pantera.