Hong Kong And The Persistence Of Memory

Press freedom and democratic values have collapsed in Hong Kong, but memories of the city that shaped my childhood remain.

Daphne K. Lee May 25 2021

From the faint memory of my kindergarten years in Hong Kong, I remember having an unexpected day off when I watched a television rerun of an elaborate ceremony. National flags and anthems were exchanged. That bold, festive shade of red, which I now understand as Communist Red, was like an incessant fever that burned through the pixelated TV screen into my five-year-old brain. It was July 1, 1997.

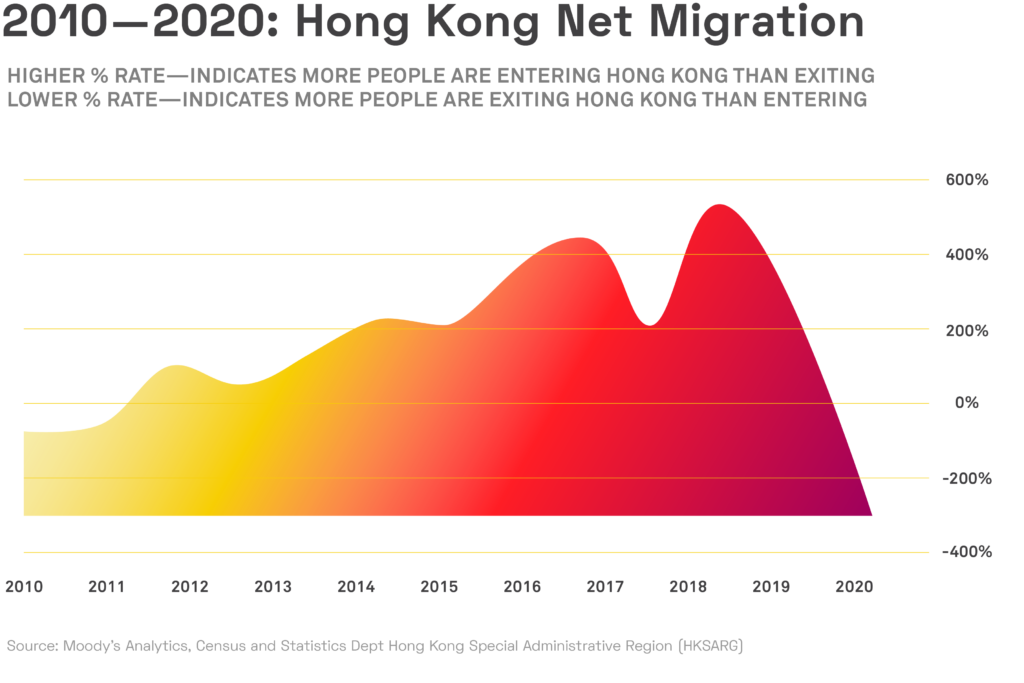

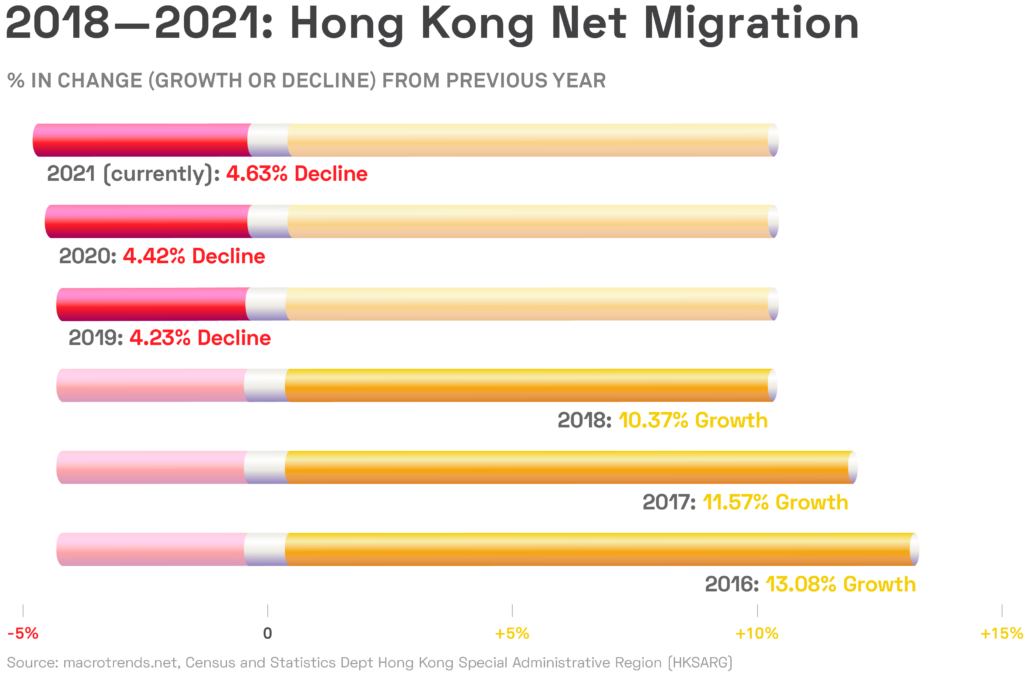

A little over two decades later, media outlets announced the death of Hong Kong. On June 30, 2020, Chinese authorities imposed a sweeping national security law to quash dissent and the city’s pro-democracy movement.

The vague legal language, a textbook example of an authoritarian law, granted Beijing extraterritorial power to prosecute any human being on this planet. According to the law, people residing both inside and outside of Hong Kong could face life imprisonment if they were convicted with crimes of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces. By virtue of writing this essay alone, I may be committing a crime.

Under the newly enacted law, dozens of activists and journalists have been charged for crimes without merits. Media tycoon Jimmy Lai, a walking symbol of press freedom in Hong Kong, was sentenced to 14 months in prison for unauthorized assembly at pro-democracy protests along with other veteran activists. Last September, the Hong Kong Police Force created a new licensing system for media accreditation, one that would redefine who qualifies as a journalist favorable to authorities. Chief Executive Carrie Lam vowed to enact a fake news law, which could be used to stifle dissent by classifying pro-democracy content as disinformation.

“During the protests [in 2019], the barrier for reporters was on the streets, in the form of raw police brutality,” said Brenda, a former Apple Daily reporter who requested to use a pseudonym for fear of reprisals. “But media censorship has since morphed into an invisible ‘red line’ and we don’t know how far it goes.”

In the summer of 2019, millions of protesters marched against the government’s controversial extradition bill, a law that would have allowed transferring criminal suspects to mainland China, where fair trials may be absent in an opaque judicial system.

The peaceful protests, however, descended into chaos as unrestrained police violence became an everyday reality. Triad members attacked protesters and bystanders in a mob while police ignored calls for help. Several protesters were believed to have died from brutal police beatings behind the locked gates of a subway station, when medics outside begged to help. In the span of six months, over 10,000 canisters of tear gas were fired into college campuses, residential streets, at unarmed black-clad protesters, at journalists. Multiple suicides have been linked to the movement as weary Hong Kongers felt increasingly hopeless about the political standoff.

Once a rising star, Hong Kong was celebrated for its economic prosperity and cultural diversity, but it is now battered by rage, resentment, and terror. Throughout much of 2019, I watched my city’s deterioration as I reported from nearby Taiwan, a democratic ally and an equally concerning target of annexation for China. I made four or five trips to the city — only a two-hour flight away — not as much as to report stories on the ground, but to catch the last breath of my birthplace that’s growing more unfamiliar by the day.

Each trip I left feeling more melancholic than the last. The streets that were once filled with selfie-obsessed tourists became wide open for anyone to roam. Some of my friends who were hopeful about the movement eventually grew jaded, looking for ways to leave. Sources that I was familiar with went dark on social media for fear of repercussions.

Staring at the media footage reeking of blood and smoke, and the many unrecognizable blacked-out profile photos on Facebook, I wondered how we ended up here. It must have been that one holiday I was naively excited about, the day that we now wish to erase from our calendar. The handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China in 1997 seemed to be a reference point for my generation to remember the before and after. That’s not to praise British colonialism, but the transfer of sovereignty was a turning point for the years of uncertainty to come.

As I watched the handover ceremony, I rushed to the kitchen and asked my mom what the special occasion was. “It’s ‘the handover’ of Hong Kong,” she said, and the literal translation of “the handover” in Chinese is “returning home.” In my brilliant toddler mind, returning home meant a joyous day off from school.

“So when will we be handed over again?” I asked, looking up at my mom in angst-filled anticipation. “The handover will only happen once,” she said.

But July 1 became a recurring holiday each year. For China, it was a day to flaunt its reclamation of Hong Kong, its continual success of the harmonious “One country, two systems” policy. For many Hong Kongers, it was an annual occasion to march for autonomy, to voice their concerns over a decline in quality of life, to lobby for — without success — basic civic rights like universal suffrage and fair elections.

As for myself, at best a bystander who watches the fire from afar, I can’t help but feel that I’ve escaped through sheer luck. Several years after 1997, my family left Hong Kong behind to different corners of the world, fleeing from the inevitable loss of freedom and stability. Those conscious decisions made by my parents, which I was too young to grasp at the time, granted me the luxury today to pen these words without fear of arrest and persecution.

Local journalists and columnists in Hong Kong are modifying their reporting methods such as writing under pseudonyms to avoid doxing. International news organizations like The New York Times are slowly relocating their staff to Taiwan and South Korea. I asked Brenda, now a freelance journalist without institutional support, if she’s worried about her future at all. She admitted to feeling anxious about the national security law’s sweeping language, but not really about her personal safety. “I’m more worried about exposing my sources,” she said, adding that she has already destroyed sensitive recordings and notes.

“Some journalists would say that if something bad happened to them, they’d be unable to keep reporting, so it’s best to protect themselves first,” Brenda said. “I still don’t know if there’s a correct answer to that.”

The stakes are rising especially for those who have only one passport and cannot afford a backup plan. As of now, an alternative future seems to be nothing but a delusion. Many Hong Kongers are reimagining their lives elsewhere, in the United Kingdom, Australia, or Canada, seeking advice on the fastest departure route.

I myself had, for years, consciously avoided media coverage of how Hong Kong was plagued by increasing inequalities and pessimism. Those struggles seemed distant or obstructive to my rather peaceful life abroad. There’s little nobility in talking about a city that I had deserted, only guilt. There’s no power in my writing, only the unrealistic desire for my city to be rid of its chains.

Daphne K. Lee (@daphnekylee) is a freelance journalist covering food and culture. She has written for several publications, including CBS News, VICE, and Nikkei Asia.