What Happens When A Meme Army Decides To Fight The Government?

The Milk Tea Alliance signals a new era in activism. But with authoritarian governments quickly rising to this emerging conflict, how will the online resistance maintain its influence?

Brian Chee-Shing Hioe May 25 2021

Fighting authoritarianism on the internet with memes. That’s one way of looking at the Milk Tea Alliance, but it could be that the online phenomenon reflects the future of protest. The unlikely grouping of the Milk Tea Alliance, which recently marked its first anniversary, consists of netizens from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand, and now Myanmar. It represents a transnational movement, whose goals are broadly pro-democracy and opposed to regional authoritarianism.

In line with much of the humor that has characterized the online exchanges between participants, the Milk Tea Alliance originates from a decidedly unserious incident. Thai actor Vachirawit “Bright” Chivaaree, best known for acting in Thai TV “boy’s love” drama 2gether, came under scrutiny from nationalistic Chinese internet users in April 2020 after they discovered a tweet in which he referred to Hong Kong as an independent country. Though Chivaaree later apologized, Chinese netizens were further enraged after an Instagram post from Chivaaree’s girlfriend Weeraya “New” Sukaram, which they interpreted as suggesting that Taiwan was also a sovereign state.

Angry Chinese trolls focused much of their attacks on mocking the Thai king and prime minister. Thai netizens, however, responded by trolling the Chinese online nationalists with self-deprecating humor and memes mocking Chinese patriotism. This included expressions of support for Taiwan and Thailand. Taiwanese and Thai users subsequently joined in on the fun, resulting in the birth of the Milk Tea Alliance, named after the distinctive milk tea beverage found in the founding countries.

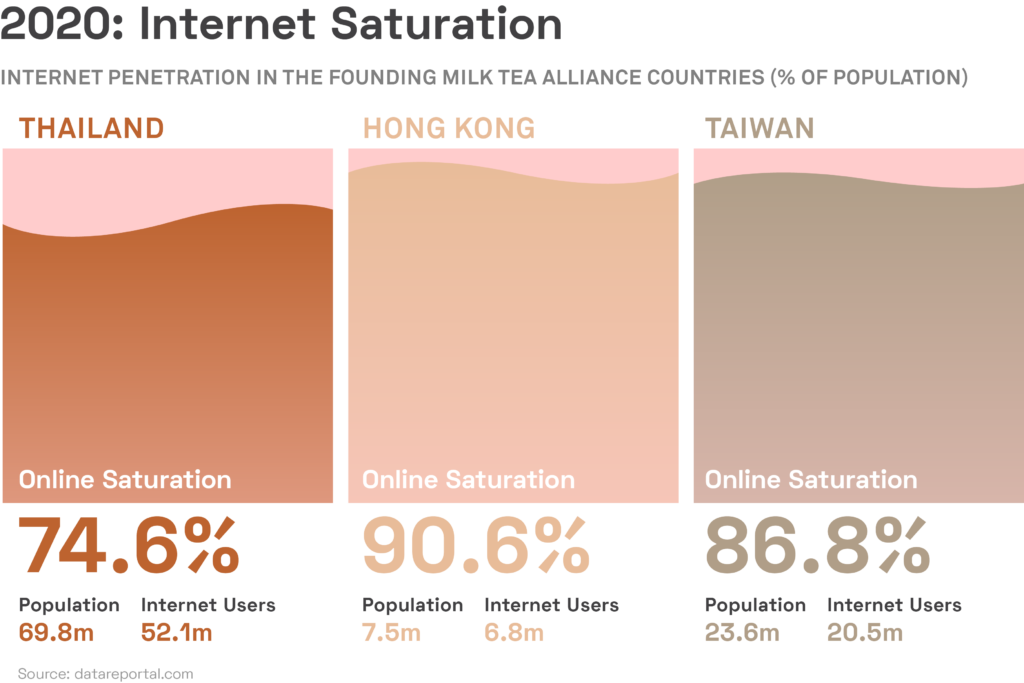

The Alliance is distinctly a consequence of a globalized, post-internet world. This can be gleaned from the naming, in that residents of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Thailand were closely familiar with each region’s milk tea beverages, either from traveling, or from widely available exports due to trade.

This connection is further reflected in the shared vernacular between Alliance members. Many of the memes exchanged are derived from familiar online formats, global pop culture, Western Hollywood films, and Japanese anime. After all, the inciting incident involving “Bright” Chivaaree transpired because Chinese netizens were already familiar with a Thai television drama.

The Milk Tea Alliance has progressed far beyond this initial incident, which has largely been forgotten, though it set the tone for much of what came later, in terms of troll culture, and the use of memes as a common language between members and its transnational apparatus. In the subsequent months, the Milk Tea Alliance framing has proved quite adaptable and expansive.

We have seen more than 11 million Tweets featuring the #MilkTeaAlliance hashtag over the past year. Conversations peaked when it first appeared in April 2020, and again in February 2021 when the coup took place in Myanmar🇲🇲: pic.twitter.com/yb0RmlTTEP

— Twitter Public Policy (@Policy) April 8, 2021

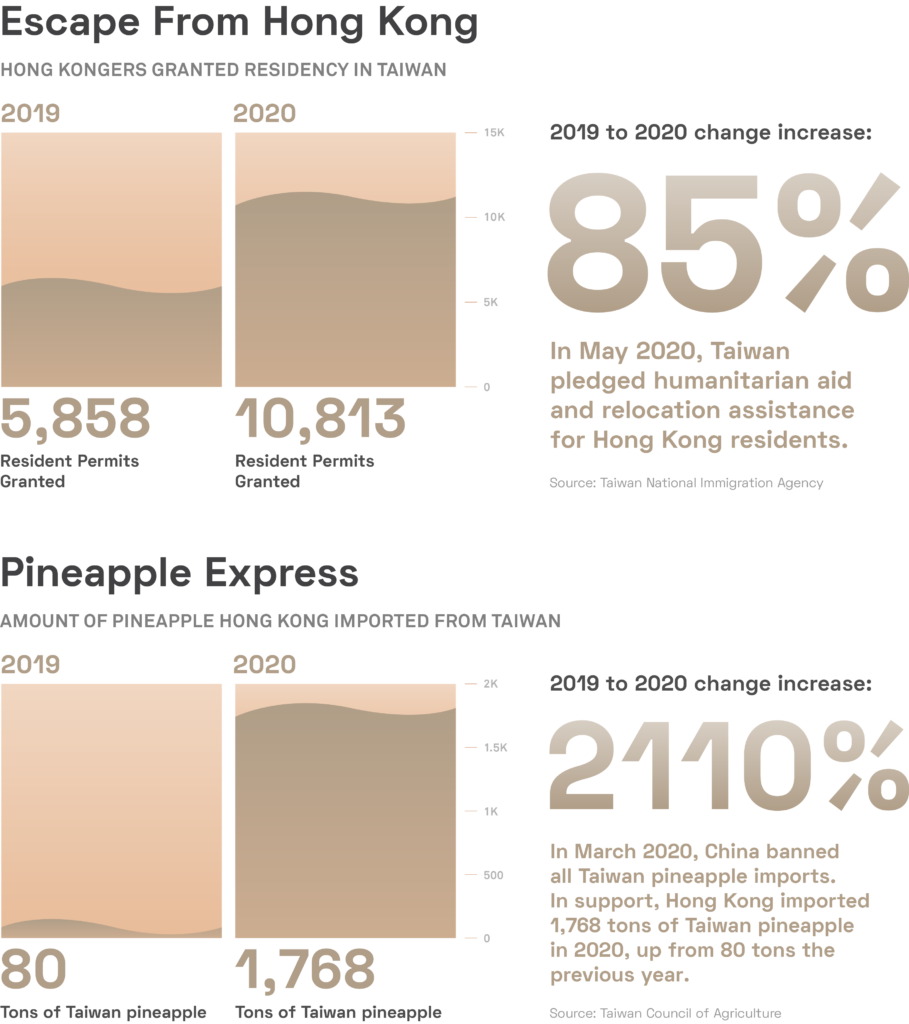

There has been a long and storied history of solidarity between Taiwan and Hong Kong, as they both share the same threat to their democratic freedoms from China. Moreover, they both have linguistic and cultural similarities. With youth-led protests having broken out in both locations over the past decade, the current affinity between them was likely shaped by Taiwanese and Hong Konger millennials consuming a great deal of each other’s cultural exports around the turn of the century. This created a shared understanding between the two, with both sides proving highly knowledgeable about the other.

However, the inclusion of Thailand brings a new element to the Milk Tea Alliance, as few would have seen solidarity between Taiwan and Hong Kong as unique. But the focus has primarily been on Hong Kong, with images of heated protests and street clashes against police being circulated regionally for months by April 2020. The protests originally erupted during the summer of 2019 as a reaction to a proposed bill that would have allowed Hong Kongers to be extradited to China, fueling fear of political persecution.

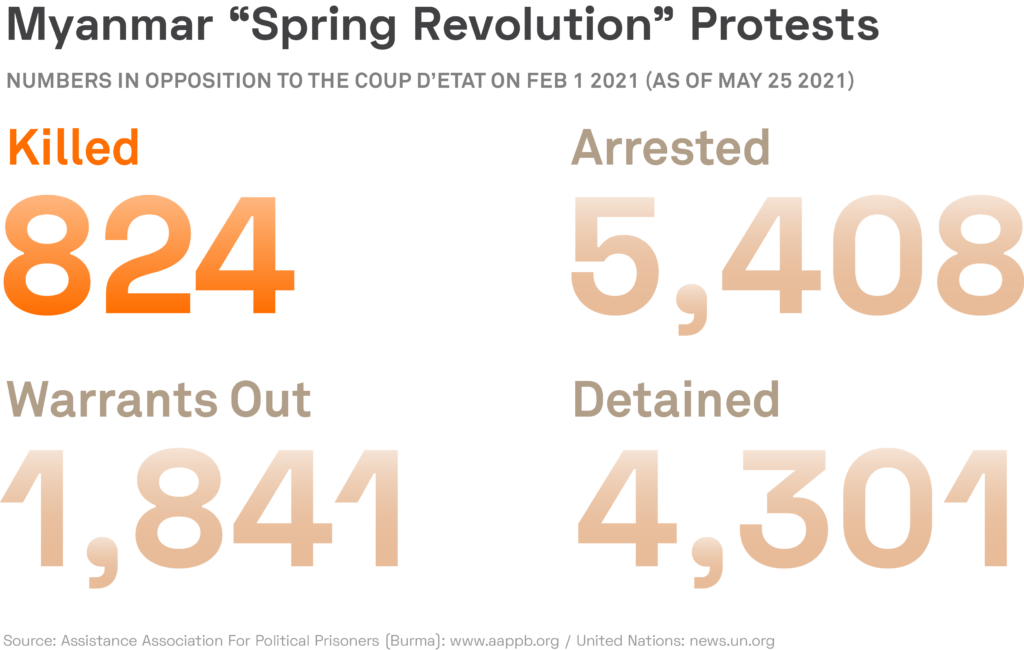

Shortly after the emergence of the Milk Tea Alliance phenomenon, Thailand saw its own set of youth-led activism. The protests in Thailand are extraordinary in their directives against the Thai monarchy, historically taboo to criticize, with those that denounce the monarchy targeted with lèse-majesté laws. This has changed with the newer protests, which were directed against the monarchy and the military junta that backs it. After a military coup that deposed Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy party, Myanmar became the latest member of the Milk Tea Alliance. It seemed like an inevitability for Myanmar to be included, as brutal protests have left over eight hundred dead.

It is probable that if pro-democracy protests occur in other Asian countries, then they, too, will be welcomed into the Alliance. Indeed, its earliest framing raised questions as to whether its ambition was more broadly pro-democracy or specifically anti-China. Some included India due to its border conflicts between the two countries.

With the outbreak of protests in Myanmar, there has been some backlash against China, owing to the belief that China backs the military junta there, which has led to the torching of Chinese-owned factories by protesters. Such views have sometimes verged on the conspiratorial, seeing as China has relations with Myanmar’s military government and is perceived as funding it, but is likely not the power behind the junta either. Ultimately, it may be that the perception of China backing other authoritarian governments in the region is a simple intimation that these governments do not have the people’s best interests in mind.

The permanent inclusion of Myanmar seems to confirm that the movement’s final premise is founded on democracy. Milk tea forever, then?

The Chivaaree meme is not the first online episode mocking Chinese nationalism that went viral. During a livestream of H1Z1, a popular online battle royale game, American streamer ‘Angrypug’ shouted “Taiwan No. 1” at Chinese gamers to “make them lose their shit”, much to the delight of the Taiwanese.

“Taiwan No. 1” is an early example of a meme that cut across borders to mock Chinese nationalists. As a whole, American gamers probably do not have any geopolitical stake in tensions between Taiwan and China. However, the virality of the event had large ripple effects in Taiwan, as the phrase subsequently became ubiquitous in Taiwan, appearing on shop stalls, in advertisements, and referenced by politicians and celebrities. Online sensations in one part of the world can reverberate elsewhere and, in this sense, this incident can be seen as a predecessor to the later, much more remarkable phenomenon of the Milk Tea Alliance – which had similarly humorous origins, but became a much more politically significant movement.

Broadly, though, the meme form is becoming increasingly influential and credible, with everything from politicized Pepe the Frog memes to the recent non-fungible token (NFT) craze shaping new asset markets. What begins as a meme can later have enormous political and social consequences.

Does the Milk Tea Alliance, in fact, reflect the future of protest? In our current climate, protests across the world demonstrate an increasing awareness of each other. When movements reach out to each other, it is uniquely through the internet.

At the same time, it may be worth raising some questions about its staying power. Transnational movements are uncommon. But even then, the Alliance also differs as it is more typical to see campaigns that shape themselves toward single-issue causes, such as anti-nuclear activists from Taiwan, China, and Japan working together, or woman’s rights groups from various Asian countries coalescing.

Transnational efforts are also often unable to directly assist each other, besides offering encouragement and support, as movements often do not materially contribute to each other when borders are in place. This is all the more so for the Milk Tea Alliance, which is primarily online; exchanges between members only occur within internet groups or through social media.

Solidarity rallies have taken place in member nations, oftentimes organized by the local diaspora of the protest location. But the commitment between members does not seem to wield enough strength for substantive support between all members, with the only notable exception being the efforts from Taiwan to assist Hong Kong in the midst of their 2019 protests, providing much needed supplies, enacting asylum measures for Hong Kong refugees in Taiwan, and Taiwanese activists traveling to Hong Kong to participate in key protest actions.

In a short time span, sophisticated tactical exchanges and counter-strategies have emerged as a key component of the Alliance’s game plan. With authoritarian regimes around the world adopting uniform policing procedures, protesters often discover counter methods by studying video clips and poring over images from other protests. Thai and Burmese activists learned how to extinguish tear gas canisters and form human barricades, thanks to widely circulated images of the Hong Kong protests. Building on that knowledge, they quickly devised their own signature tactical innovations, such as using inflatable water floats as shields from riot police.

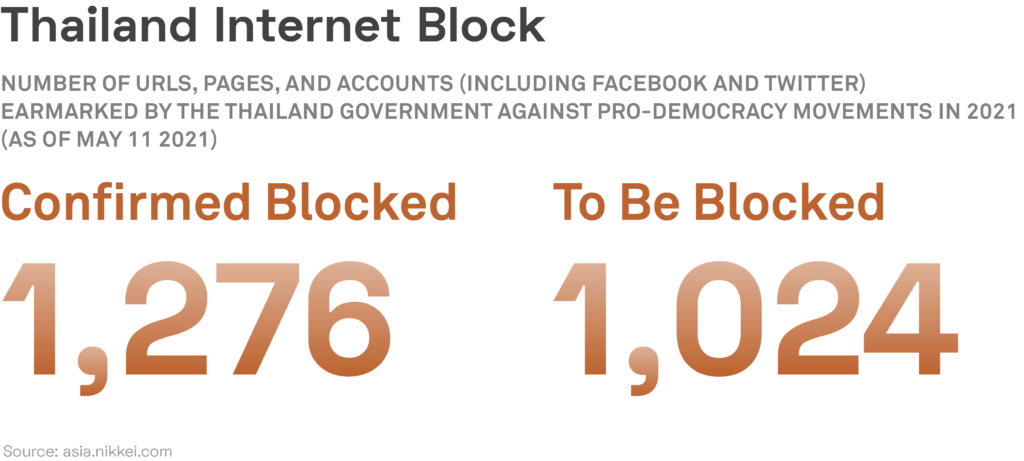

Increasingly, there are growing parallels between online and offline social movements. The nature of the Alliance is intrinsically similar to that of the physical protests which have taken place in Thailand, Myanmar, and Hong Kong, with participants frequently shrouded in anonymity, obscuring their faces and other distinguishing features to avoid being identified through facial recognition technology. Most contributors are anonymous accounts applying persistent pressure–once they are banned on Twitter, they return with new profiles. Though it remains to be seen how effective such networks will be, new networks have formed in this manner, as international netizens befriend and exchange ideas through multiple disguised Twitter handles.

Modern protest movements in Asia have begun to shift away from singular and recognizable leader figures that can easily be targeted with arrest, which can quite effectively decapitate the command structure. The shift toward anonymity and collective decision-making—the Hong Kong protests notably utilized the online forum ‘LIHKG’ as a vehicle for collective deliberation on tactics—may prove to be a blueprint.

Future movements may not be so easily divided into distinctly online or offline efforts, but may involve a significant degree of online-offline interfacing. Anonymous Twitter profiles can still be targeted. Last year, a large wave of Hong Kongers deleted their Twitter accounts to prevent being marked by national security legislation criminalizing separatism. The same risks may apply to both online and offline spaces, as online communities have proven to be increasingly influential for real-world assembly. Alt-right platforms such as Parler have had a crucial role in recent political clashes in the U.S. The online collective Anonymous has intervened in various key political events globally, and the power of Reddit groups is increasingly felt in the financial industries as retail investors upend the stock market.

Interestingly, authoritarian governments are responding by employing similar tactics. For years, the Chinese government’s ‘50 Cent Party’, consisting of online commenters supposedly paid .50 RMB per post, have harshly attacked anything critical of the CCP. The 50 Cent Party outlines the effort that the CCP place into maintaining the appearance of organic support; this despite the fact that members routinely operate on social media networks that are banned in China, such as Facebook and Twitter.

Similar to the 50 Cent Party are the ‘Little Pinks’, who are nationalistic Chinese users such as those initially targeted by the Milk Tea Alliance. Mostly young and female, well-educated, and online savvy, the Little Pinks spin jingoistic posts on micro-blogging sites and across social media, fiercely defending China and the CCP. Many are studying abroad, with full access to all the apps and platforms. It is thought that Little Pinks were among those initially triggered by the Bright incident, with young Chinese women among the viewers of 2gether. With its 50 Cent Party and through state-run social media accounts, the Chinese government has stoked the fire of online nationalism when useful.

Also notable is the rise of online ‘tankies’. Tankies has long been used as a term to describe residents of Western countries that support authoritarian non-Western governments, and recent years have seen the rise of a new wave. Divergent from previous tankie generations, these are primarily Gen Zers that have been recently politicized, with increasing support from the CCP. This would align with broader fifth column efforts by the Chinese government, often referred to as the United Front. In contrast to the self-mocking humor of the Milk Tea Alliance, the tankies rally around an idealized China, asserting its cultural and civilizational superiority, and its territorial claims over its neighbors.

The confluence of many of these online subcultures rests in the common goal of information influence and news aggregation. The Alliance effectively operates as a network for the dissemination of content in real-time, as images of police violence and its contextual narratives are quickly circulated and reported on by global media, allowing for international pressure on the actions of an authoritarian government. Concurrently, governments try to contest the narratives of pro-democracy groups by using their online troll army. The Alliance serves as a means by which pro-democracy and pro-government forces contest their respective political truths, and what emerges is a larger pattern of convergent tactics between both authoritarian state actors and those contesting them.

Without question, the Milk Tea Alliance will be increasingly targeted moving forward. In particular, Chinese state-run media has sought to frame the Taiwanese government as implicated in secretly orchestrating Milk Tea Alliance. A December 2020 case involving two Taiwanese men arrested for circulating Chinese disinformation after traveling to China to receive training from the Chinese government, proved another sign of this. The two men fabricated false documents that were intended to suggest a link between the U.S., Taiwan, and the Milk Tea Alliance.

Indeed, authoritarian governments have sought to frame the efforts as “color revolutions” covertly planned by Western governments seeking to delegitimize protest activism, suggesting they are inorganic, and funded by foreign interference. Contrastingly, Alliance activists draw legitimacy from each other, by claiming to be part of a broader, universally human struggle that has emerged in multiple places at once.

Does it help to examine history in this case? In the early 2010s, the Arab Spring was used as a similar context to characterize the wave of protests that erupted across the Middle East, with social media hailed as a positive global force that allowed for democratization. However, the Arab Spring led to assessments that now seem overly optimistic, and ten years later, these countries are again mired in internecine conflict. It remains to be seen as to whether the Milk Tea Alliance will suffer a similar outcome. What began as an amusing online meme feud grew rapidly to a vast, decentralized, and forceful protest movement fighting authoritarianism. The wit and humor have widely remained intact, as has the resilience. But the continued campaign may be easier said than done.

Brian Chee-Shing Hioe (@brianhioe) is one of the founding editors of New Bloom Magazine and a freelance journalist and translator based in Taipei.